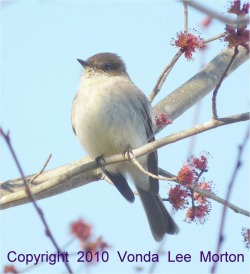

Thanks to all three of you who donated; only two actually ventured a guess. One agreed with my suspicion that it might be a chipping sparrow; the other guessed sedge wren, which isn’t native to Georgia. Based on the resounding lack of response, even after the local paper ran a story on our albino phoebe and plugged the contest, I’d say contests were not something y’all’re interested in. Probably won’t try that again…

RSS Feed

RSS Feed