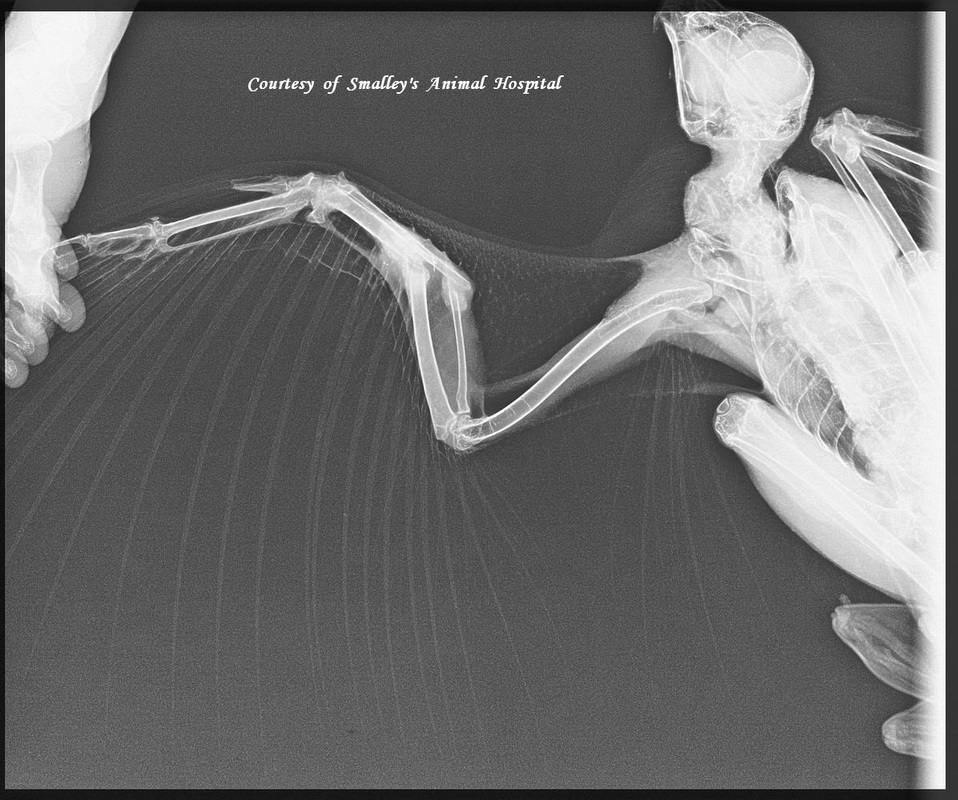

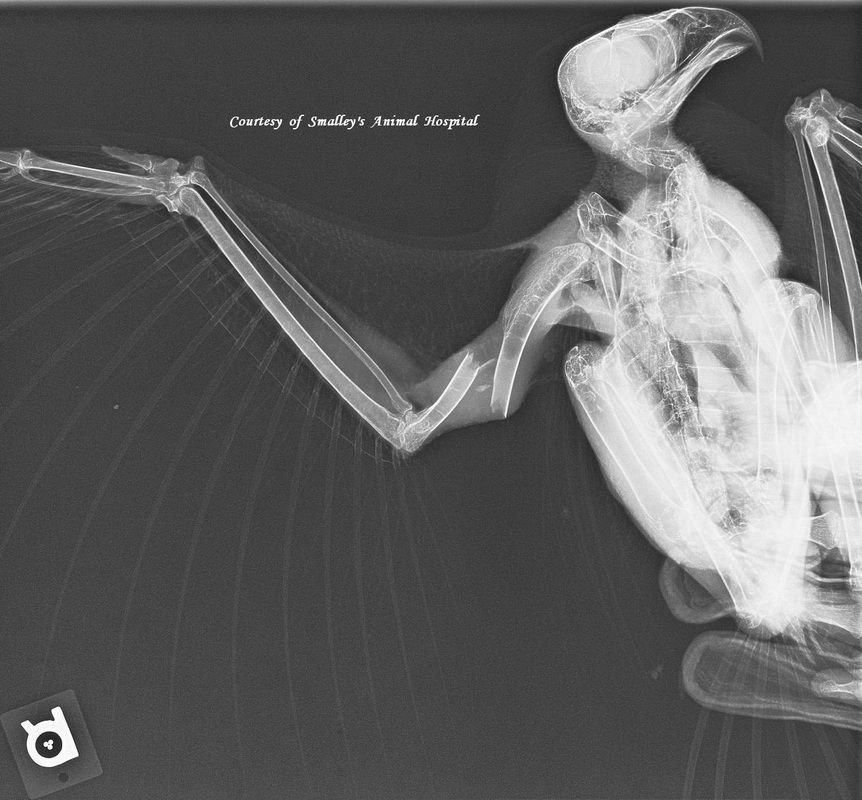

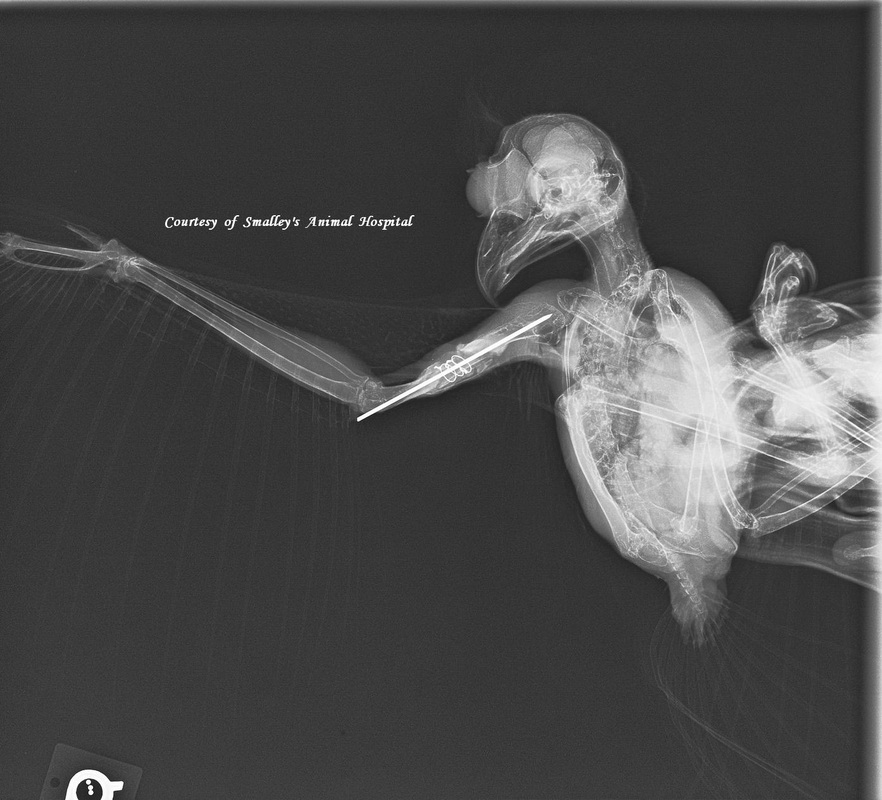

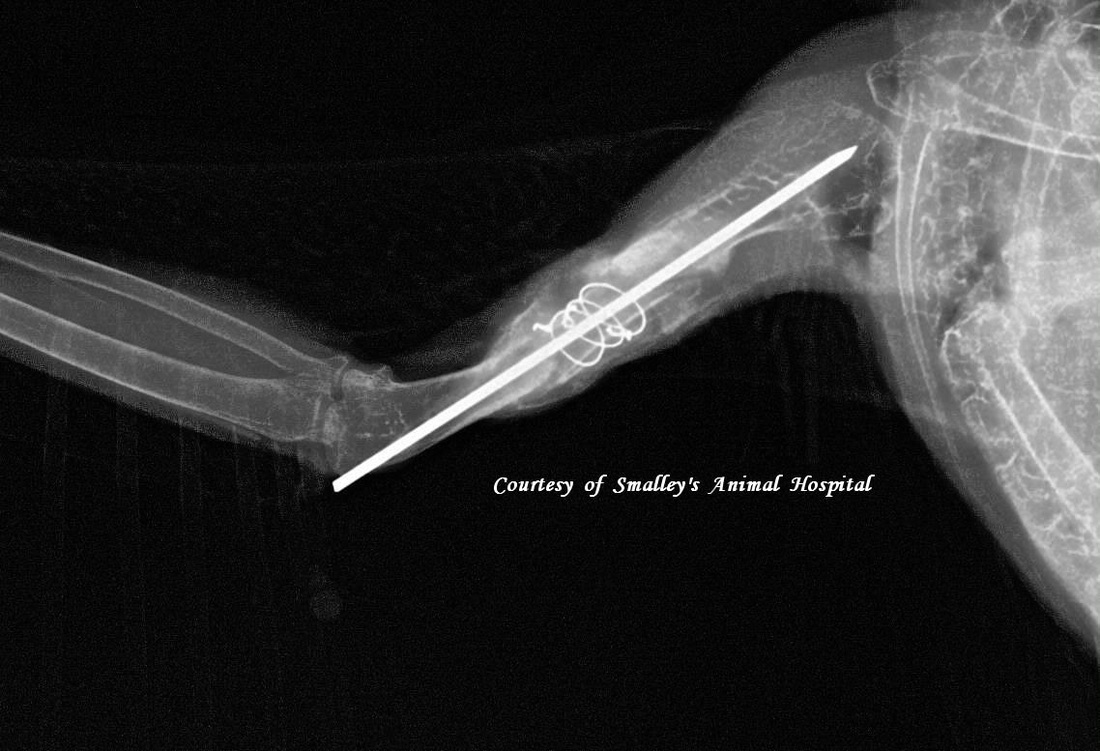

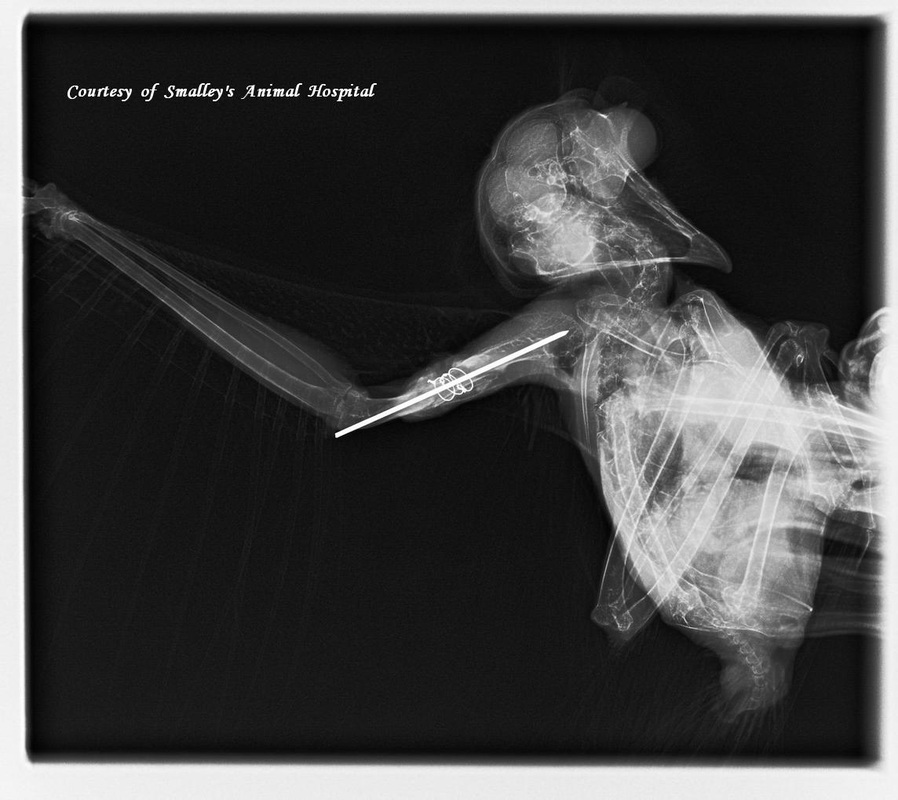

Below is his latest x-ray.

Vet Jim Hobby of Smalley’s Animal Hospital and I were delighted when the towhee’s x-ray showed no fracture. His wing does droop a bit, though, so it could be badly bruised or he may have a coracoid fracture, a common injury in window strikes. This type of fracture cannot typically be felt and usually doesn’t show on an x-ray, so the general treatment is to confine the bird’s movements for a couple of weeks to allow it time to heal on its own.

Sir Towhee is NOT happy about his confinement, but he IS eating well, so we’re just gonna give him the time and support he needs to heal.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed