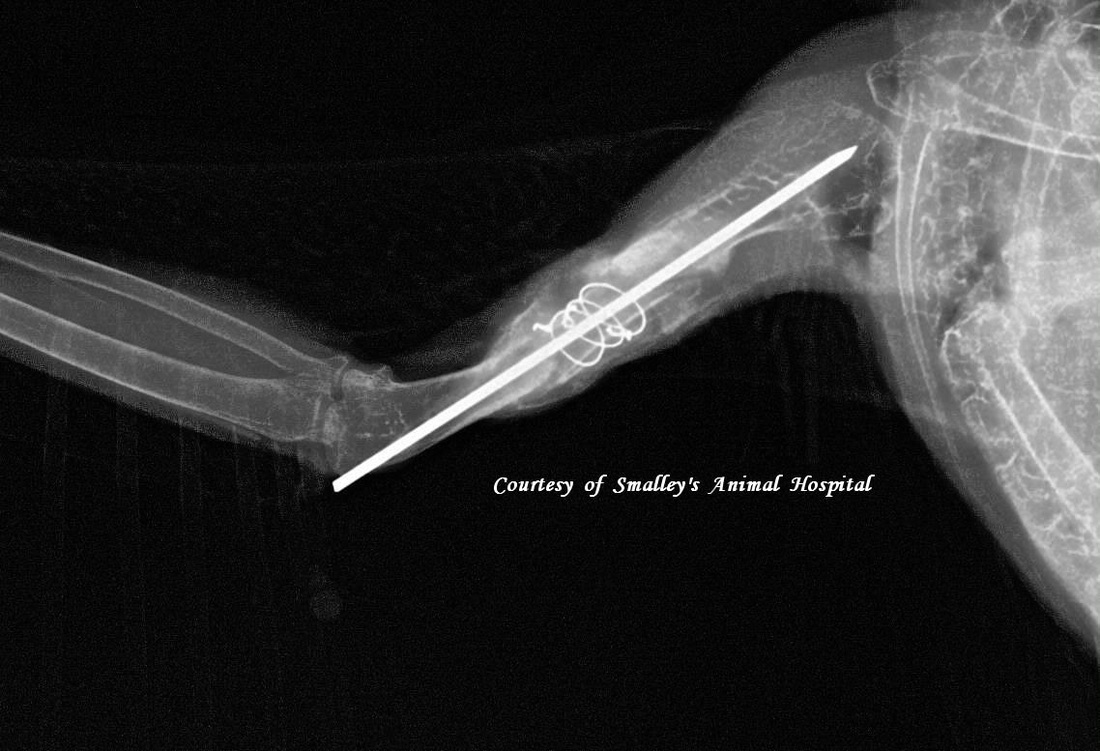

Actually, it was a fairly typical week: life and death, highs and lows. Beginning with the “mediums”, let’s update the barred owl situation. His latest x-ray shows the bones still healing, albeit slowly. We guesstimate another two weeks, minimum, with the pin in place. Could be longer, but Lord knows Sir Barred and I both hope not. As I mentioned last week, he’s a pretty unhappy camper—and with good reason. See, his hormones are in full swing. This is the time of year he should be out looking for a mate, not sitting in confinement. His hormones scream, “Find a mate”; his broken, pinned and healing wing says, “Whoa there, buddy; you ain’t goin’ nowhere just yet!” Can’t really blame the poor fellow for being a bit of a basket case at this point!

How does finch eye spread? Birds, when they’re done eating, wipe their beaks on the branch, the feeder—whatever is at hand to serve as a “napkin.” Infected birds thus leave behind germs to infect other birds. Feeders are prime breeding grounds for diseases like finch eye. While it is treatable if caught early, it also has a tendency to recur. Some rehabbers attempt to treat; others euthanize because of the high rate of recurrence. For this bird, it was a moot issue, obviously.

I explained to the rescuer that he needed to take down his feeders, clean them thoroughly with a mild bleach solution (1 part bleach to 10 parts water), and leave them down for a few days. Honestly, I recommend this as a routine weekly maintenance task for anyone who has feeders. My suggestion is to have backup feeders, so you can rotate them out: while one is being cleaned, you already have the one you cleaned the previous week to replace it with. This rotation method works well with hummingbird feeders, also.

And finally, while this isn’t, strictly speaking, a rehab story, it’s just too neat not to share. Hognose snakes are non-venomous, very shy, and will often play dead when threatened. Their name comes from their upturned noses. There are three major subspecies, Western, Eastern and Southern. In Georgia, as is the case in much of the South, the Eastern and Southern subspecies overlap, with the Southern being the smaller of the two. Southern hognose snakes are officially listed as threatened in Georgia, and I haven’t seen a hognose snake of either Georgia species in about a decade.

So you can imagine my delight when I found a baby hognose snake—and I do mean baby, as in recently hatched—in my yard last week! He appears to be an Eastern hognose—the Southerns have a more pronounced upturn to their snouts and their bellies are lighter colored. According to my research, the eggs laid in summer hatch from mid-September to mid-October, and the hatchlings are six to eight inches long. As you can see in the photos below, my guy was around or just over the six-inch mark, making him a very recent hatchling. The exciting thing to me is that somewhere nearby he has siblings! I’ve been manically checking my yard since finding this “leetle feller” to see if any of his sibs also wander into the yard, but so far he’s been the only one I’ve seen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed