When LWR initially received word that a “big bird” was in an area fast food parking lot, several counties away, I explained to several callers what needed to be done to get the bird to me. It took a DNR biologist and two LWR volunteers working together to actually get the bird to LWR, however, with the biologist fearing it had a wing fracture.

And what was the bird that caused all the ruckus? A migrating sandhill crane!

You see, the sandhill wasn’t thrilled that we “manhandled” him so rudely: I had his head and feet; Richie had his wings and body; the sandhill had had enough. He scratched Richie and buried a claw deep in my arm, but we by-God got our x-rays. And the rehab gods smiled on us: he had no fractures!

The volunteer spent the better part of her day driving to sandhill 2’s location and hemming it up to be boxed for transport. She met other volunteers who “ponied” the second sandhill to LWR, where we immediately placed her in the pen with our older-by-a-day guest. He had been vocalizing frantically, but when his new paramour entered the pen, he was gobsmacked by her beauty and immediately began the purring vocalization that even those of us with no prior sandhill experience recognized as conversation.

So…to Facebook again to reiterate the plea for calls about larger flocks to integrate these two into. Our plan was to find a flock coming in to roost for the night and place these birds with that flock, so they’d all leave together the next morning.

In the meantime, I’d contacted the two major crane research groups in North America, Operation Migration in Ontario and the International Crane Foundation in Wisconsin. Heather at Operation Migration and Anne at ICF liked Plan A, above, so I asked about our proposed Plan B—to release the pair as a “flock of 2” if necessary. Both researchers said with two birds this was feasible and acceptable, although Anne with ICF did recommend keeping them a few days to give them time to pair-bond since they were already doing the purring and sticking pretty close to each other.

With no word on any large flocks nearby, we’re set to implement Plan B within the next couple of days and wish these lovebirds well as they head north for breeding season.

I wasn’t prepared for what happened next.

Fifteen minutes later, she called back. The rehabber I’d blithely and trustingly referred her to for help told her that "cat-attacked squirrels don't usually live anyway" and refused to take it. OH. MY. GOD. You have no idea what that did to my blood pressure.

I told the rescuer that if the squirrel had no serious puncture wounds he had a VERY good chance at survival with the proper meds and that I'd meet her and take this poor baby. I mean, the lady was trying to do the right thing; she said the squirrel was active and it only had scratches. I could not in good conscience let her sit there and watch it die from TREATABLE injuries.

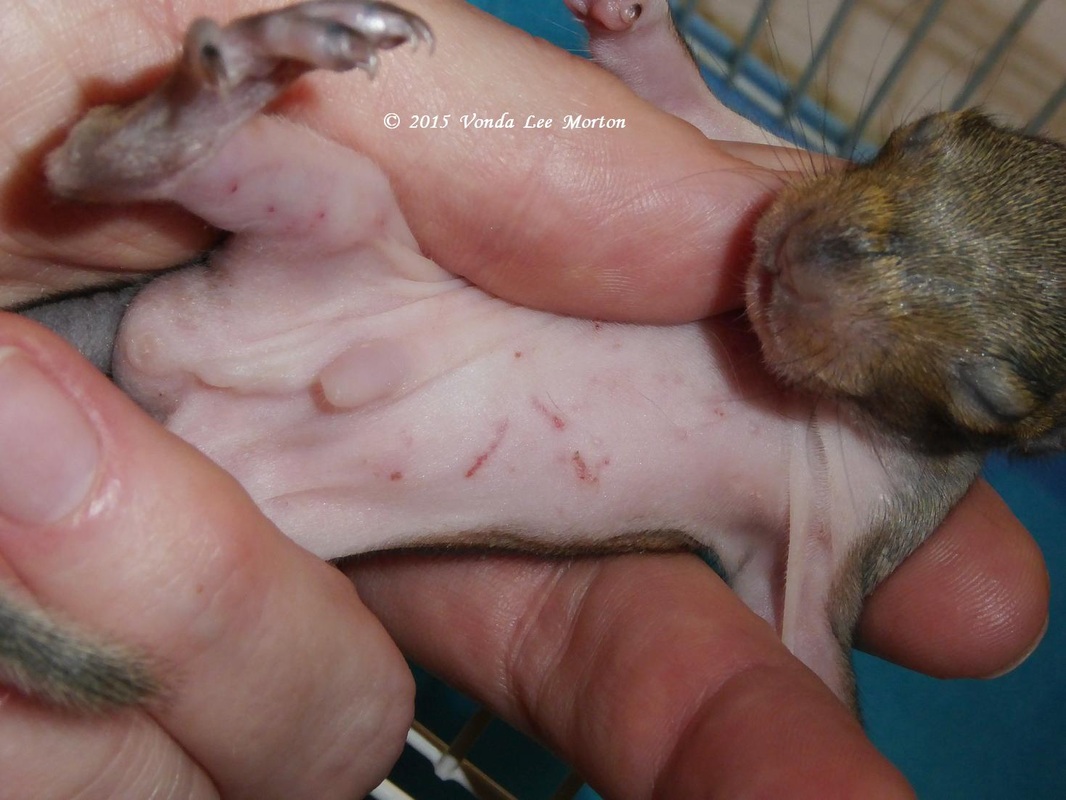

The approximately four-week-old male gray squirrel was slightly dehydrated on intake and his belly and flanks were scratched up but he readily took formula and his wounds are already almost completely healed. He’s also gained over 10g since intake and wiggles about excitedly when he hears me open his little cage to feed him.

In more worrying news, the cedar waxwing, while getting increasingly restless, still has no real lift. He is fluttering farther before drifting to the ground but once he’s grounded he makes no attempt to fly. Coracoid fractures usually heal to allow unfettered flight, but there are always exceptions. I’m beginning to suspect this guy might be that exception. I hope not; I hope to have good news to report on him next week. But the doubts keep rising…

And despite a week of utterly crappy weather, my nephew Alex, my father and I did manage to get the remainder of the predator guard down in the raptor flight and doors ready to hang on both flights. That leaves the pea gravel and fill dirt, perch installation and other minor tasks easily handled by one person, so…by next weekend I hope to have these pens fully ready for use!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed