Strange combo, huh? Not as strange as you’d think. Read on...

A few days after our last update, I received a gunshot hawk - adult male redtail; gorgeous bird. He still had a pellet lodged in the wing the shotgun had shattered, and infection had already set in, so we had no choice but to euthanize. Because this bird had been shot, I also had to report it to the feds and am still awaiting word from them on what we need to do with the corpse, which Smalley’s is very kindly storing for me.

That brings me to one philosophical musing...or rant, if you prefer. Anyone who would shoot a hawk – any animal, for that matter – for their own perverted pleasure deserves the same fate. Unfortunately, since the coward who shot this bird left him for a 17 year old girl to find and bring to me, the cretin will probably never see justice...at least not in the courts of law. We can only hope that his karmic "reward" is to become the victim of a hunting accident.

Yeah, I know – sounds cruel and inhumane. Excuse me – what do you call shooting a hawk for the heck of it – and in violation of federal law, I might add – and then leaving him to die?? I say let the punishment fit the crime, but that’s just my own Hammurabian sense of justice.

There is a bright side to this, however: the young lady who found the hawk did everything right. Had the bird been savable, her quick thinking and fast action would have ensured he had a fighting chance, and I hope that in the future she continues along that path of caring action for our native wildlife.

The very next day – literally, at midnight – I received a call from another female who’d hit a young bobcat on the way home from work. Here again is an example of doing the right thing. She could have left the cat to his fate on the side of the road and gone home to bed; instead, she called me and asked me to come get the cat, even though it meant she had to stand in the cold and wait for me to arrive.

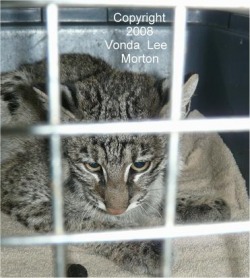

When I arrived at the spot where she waited for me, the bobcat was still in shock, so with her help to stabilize the spine, we were able to load him into my carrier. Since there was what appeared to be fresh blood in his poop, I honestly didn’t expect him to make it until later in the morning when Smalley’s opened. He also had a deep gash on his right shoulder that would need more advanced treatment than I was capable of providing, so I made him as comfortable as possible and hoped for the best come morning.

To my surprise, he was awake and slightly more alert, although still a bit shocky, when I got up, so as soon as Smalley’s opened, I called and arranged to take him in ASAP. When I got there, Peggy Hobby sedated the cat so she could perform a proper exam, and she did X-rays. Usually I help restrain the animals for X-rays, but our young feline was out cold, so I was able to snap a photo while Peggy worked.

Peggy and fellow vet Shelley Baumann had conferred over treatment for the bobcat, whom Peggy estimated at 6 months, based on his teeth, and had agreed that if the X-rays were good, the shoulder could be stitched up so I could transfer the cat to a rehabber licensed for rabies-vector species. (I’m not RVS-licensed.)

Unfortunately, the X-rays came back with bad news. The spine was in excellent shape, but the small bone at the back of the heel that the Achilles tendon attaches to was in three pieces. Peggy said that this sort of injury would require specialized surgery and that in the instances where they had referred animals for that surgery, the recovery was never 100%: the animals could never put full weight on the injured heel again. For a domestic animal, who has human servants, that’s not an issue; for a wild animal, that’s a death sentence.

None of us were happy, and Peggy & Shelley even debated going ahead and seeing what they could do in-house before deciding it was unfair to the cat to put him through any more pain knowing that in the end, we’d have to euthanize when he couldn’t use that leg. A bobcat who can’t run and chase his prey can’t survive in the wild.

That brings me to philosophical musing number 2: it’s not about the QUANTITY of life we can give a wild animal; it’s about the QUALITY. If I can’t return an animal to the wild and know that s/he has as good a chance at survival as before s/he came into my care – a better chance, actually, in the case of young ones who would have died without intervention and supportive care – then I’m not going to prolong his/her life just because I can. And a life in captivity just isn’t doesn’t strike me as a good option. I talk frequently about getting a permit to keep an animal as an educational animal should it be nonreleasable, but I always end up doing what’s right for the animal, which is releasing it the only way I can when a return to the wild isn’t possible. A cage, no matter how gilded, is still a cage, and no wild animal can live its life as nature intended while in captivity.

Having said that, there are those rehabbers who have nonreleasable animals come in with very calm temperaments and/or good personalities, animals they know will make excellent educational resources. I have no issues with that: it’s a personal call, and I haven’t had an animal come yet in that I think would make a good educational resource. If I did, you bet I’d apply for the proper permit and provide the closest thing to a life in the wild that I could for that animal, always with some degree of guilt that I couldn’t give the animal the freedom it deserved.

Bottom line, though: unless it’s an exceptional instance, I’m always going to opt for a humane end to suffering over healing physical wounds and prolonging psychological suffering. All too frequently, euthanasia is the only way we can give an animal back its freedom. Do we like having to make that call? No, and it’s not an easy decision, either, but after many long conversations with other rehabbers, I can assure you that we know in our hearts that it’s the right call.

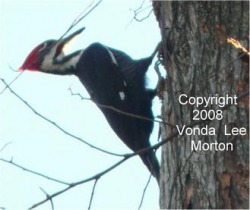

Philosophy lesson over, boys & girls, and I’ll leave you with these photos of a pileated woodpecker to lighten the mood somewhat. This fellow was so engrossed in his hunt for tasty grubs that he allowed me to snap quite a few shots. They’re not the best in the world because my zoom only goes so far, but how often do you get a good look at these rather shy birds? (If you’re not familiar with ‘em, their call is reminiscent of Woody Woodpecker...or an escapee from the loony bin!)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed