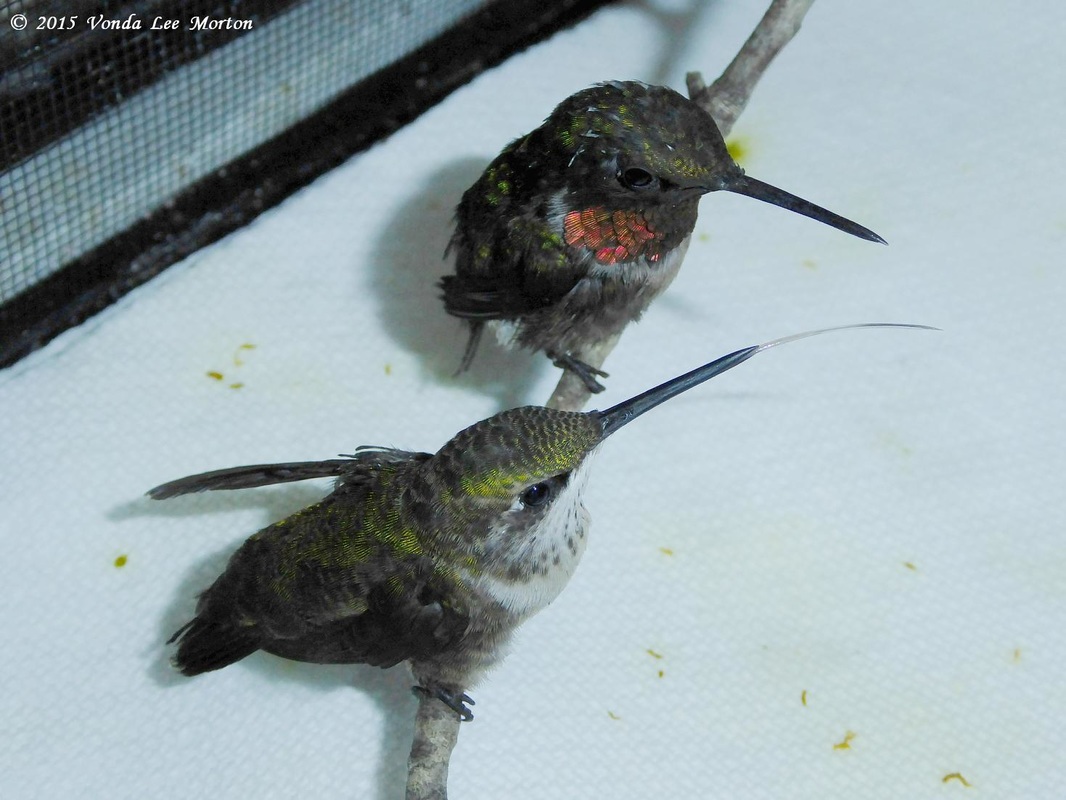

The other two hummers continue to do well but still show no signs of being able to sustain proper flight. We’re in a time crunch now; October is usually the latest hummers pass through Georgia during migration, so these two need to get their acts together soon.

The screeches are being typically screechy, glaring and beak clicking and mouthing off. And the female is finally starting to get her adult head feathers, so she’s gone from cute fuzzy-head to scruffy half-fuzz, half-feathers this past week. The male perches in one of the flight pen corners and glares at me; the female flits from perch to perch, weaving and bobbing to see what I’m putting out for supper. Next step is to test these two on live prey; if they can snag their own prey, they’re good to go!

I had someone recently—not a rehabber—call wildlife rehab a hobby. It took great self-restraint not to choke them on the spot.

Here’s the Merriam-Webster definition of “hobby”: a pursuit outside one's regular occupation engaged in especially for relaxation.

Hmmm…so what does Oxford have to say? An activity done regularly in one’s leisure time for pleasure.

Interesting…Cambridge? An activity that you do for pleasure when you are not working.

So hobbies, then, while often expensive, are undertaken with the expectation of pleasure and engaged in in one’s free time—i.e., when not working at one’s “paying” job.

Anyone see the issue I have with calling wildlife rehab a “hobby”? No? Well lemme explain it for ya, then.

Wildlife rehab is a passion, a calling, a way of life. It is NOT something engaged in as an afterthought—“Oh look, I have a couple of hours free; I think I’ll rehab some birds” or “Can’t wait till this weekend to rehab a bird or two.”

Rehabbers do experience pleasure in what we do; there’s no denying that. But the heartbreak outweighs the pleasure by far. Do you know of any other field where the expectation going in is that you’ll lose 50% of your intakes every year? This is the harsh reality of wildlife rehab.

Most people’s “hobbies” don’t entail getting peed, pooped and puked on; bled on; scratched, bitten and clawed; and seeing animals mangled beyond repair.

Birdwatching—that’s a hobby. Wild bird rehab—that’s a vocation.

It matters not that the rehabber usually doesn’t receive a salary (and the vast majority of rehabbers around the globe are home-based, not working in large centers); the fact of the matter is, rehabbers are trained professionals.

Do we hold down “paying” jobs? Yeah, most of us do, because without some sort of income we can’t care for the wildlife we receive. It’s expensive, as most of you well know by now. But most of us work those paying jobs around our wildlife rehab, not the other way around—which doesn’t exactly fit the definition of a hobby.

As for relaxation—well, you tell me: What’s so relaxing about feeding a dozen or more baby birds every 15-30 minutes 12-14 hours a day for 5 months out of the year, fighting with an angry raptor to feed or medicate it and treat its wounds, or watching a bird you’ve struggled to save give up the fight and having to euthanize it? Relaxing, my arse!

No rehabber will deny the pleasure—the sheer joy—of a successful release. That’s what keeps us going—the ones we get to release after weeks or months of hard work. But the physical, mental and emotional tolls, to say nothing of the financial drain, hardly qualify wildlife rehab as a mere “hobby.”

Please feel free to slap the fool out of anyone you hear say that (bearing in mind, of course, that no rehabber will have the money to go your bail; it’s all been spent on the wildlife in their care).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed